How to bring SMSFs back under control? Take a SIPP.

We had an enthusiastic (and alarmed) response to last week’s Trialogue example of an SMSF geared to the hilt to buy a crane. It’s pretty clear that there was a lack of awareness of the more adventurous SMSF strategies being proposed out there.

A couple asked “ok, so what can we do about it?”. Very reasonable question. We think there are two parts to an answer:

– Regulatory responses (ie how do we rein in the more extreme practices)

– Commercial responses (do we try and beat ’em or join ’em?)

This week we look at a possible regulatory response – but this will require lobbying by our readers and others leading the industry bodies, wealth divisions of the banks, AMP / AXA, and largest not-for-profits.

The problem here is that the Super System Review had the policy opportunity to establish some sensible SMSF boundaries, and fluffed it. It’s harder to revisit the issue when the official all-clear has been given.

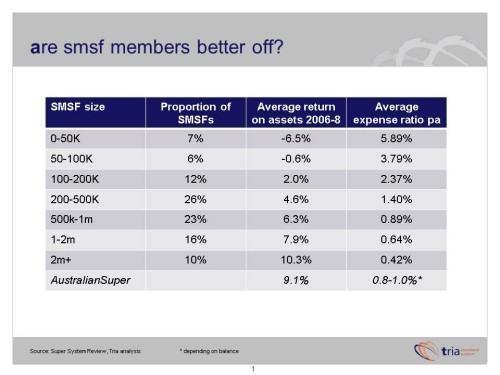

But there clearly was a problem, even then, simply looking at cost and efficiency issues. Today’s table comes from the Review’s own statistics, and compares the average returns and expense ratios for different size SMSFs, compared to AustralianSuper as a proxy for a widely available collective alternative. It was pretty obvious that the typical SMSF below $500,000 in assets has much higher costs and much lower efficiency than a large collective fund. How that conclusion was never reached by the Review is something of a mystery.

For an effective regulatory response, we need to look at tighter investment strategy requirements, or tax treatment of certain assets which achieve the same outcome.

Happily there is a precedent that we can use – the UK self-invested personal pension (SIPP) regulatory regime. Given the suspicious resemblance of FoFA to the UK’s new RDR regulation, this is less of a leap than you might think.

SIPPs are offered by both collective funds, and as a stand-alone structure (ie comparable to a SMSF). They have considerable flexibility in terms of what they can invest in, and they can borrow as well (but only to a maximum of 50% of the net assets of the SIPP account).

There is a further crucial difference – the concept of “taxable property”. Taxable property includes residential property (and related land), and all forms of movable property including collectibles and machinery. There are look-through provisions which deal with avoidance by holding such assets in structures like trusts.

Technically a SIPP can invest in taxable property assets. But as the name hints at, there are punitive tax rates of 40% on returns from such assets, which in practice knocks them out. Collective SIPP providers simply do not offer such exposures.

We think taxable property is an elegant concept – in one swoop we could solve the SMSF problems we already see relating to collectibles, the problems we are going to see with heavily geared residential property, our notorious crane example, and no doubt endless future kooky ideas.

It would establish reasonable limits around the investment practices of SMSFs, while still permitting a wide choice of mainstream investment strategies. Importantly it would mean that tax concessions are not used to subsidise art collections, other exotic assets, or high risk strategies which represent a bad deal for the tax payer.

Looks like the Brits have another gold medal here. We should learn from it.