Bottom line vs triple bottom line: making ESG more sustainable

The role of Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors in investment strategy is growing, with the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance sizing the responsible asset management market as $23trn at the start of 2016. This represents a growth in AUM of 25% since 2014.

In our institutional asset owner insight programs, we see an increasing number of investors implementing ESG principles, due to either a desire to get to grips with the issue, or pressure from stakeholder groups. In the Invesco Global Asset Management Study 2017, 33% of sovereign investors expected ESG to increase in importance over the next 3 years. In retail markets, most platforms (both pension and non-pension savings) now offer ESG options.

However, ESG comes with unique challenges. The justification can be unclear (indeed it is not fully accepted even now), its remit can be confused, and the degree of enthusiasm from beneficiaries and investors is not universal.

In short ESG could do with becoming more…well…sustainable.

Significant ESG influenced investment strategies date from the mid-20th century when certain US pension funds started identifying investments with desirable social objectives and considering the social impact of their portfolio. ESG became mainstream in the 1970s with South Africa’s apartheid regime leading to widespread divestment – what we would now call a ‘negative screen’.

Today, strategies target a variety of success metrics across interpretations of ESG factors, including carbon emissions, employee diversity and executive remuneration.

However, many institutions are not permitted to adopt ESG strategies at the cost of investment returns, and NMG’s research indicates that only a small proportion of retail investors are willing to accept a lower return in exchange for ESG benefits. This has led to extensive industry research into the investment performance of ESG strategies, attempting to identify an “ESG premium”.

Due to the vast amounts of performance data required for robust attribution of ESG strategies to performance, the weight of research has focused on equities. Within equities, there is a clear weighting of confidence in investor ability to generate outperformance through each ESG component:

1. Governance – “better oversight and engagement lead to better returns from enterprises”

2. Environmental – “investments that harm our world may prove to have no long-term value”

3. Social – “firms impacted by social controversies may suffer significant reductions in value through community, regulator, and government responses”

While confidence has developed around Governance, even this has faced challenges, primarily through the rise of passive investing. By definition, passive investors attribute a predetermined weight to an index constituent. Without an ESG remit, due to the lack of a credible disinvestment threat, passive managers are limited in their ability to effect change other than via engagement and voting of holdings (which some are doing).

So where is ESG industry? In the short-term, investors which have commenced the journey will look to widen the application of ESG strategies across the portfolio. Fixed income is the obvious next step, with growing datasets of corporate bond performance allowing for more accurate attribution of performance to ESG factors. Indeed, many debt-issuing corporations also issue listed equities, and investors are able to correlate sell-side equity data to corporate bond performance.

In fact, there are several reasons why fixed income can be more attractive than equities for ESG implementation:

- Fixed income offers the chance for investors to finance the growth of ESG compliant businesses and to withhold funding from those that don’t comply.

- There are niche but growing opportunities in climate, social, and green project bonds.

- Fixed income strategies (when held to maturity) offer investors a clear view of future returns, which is important as long as the justification of ESG strategies remains through an investment metrics lens.

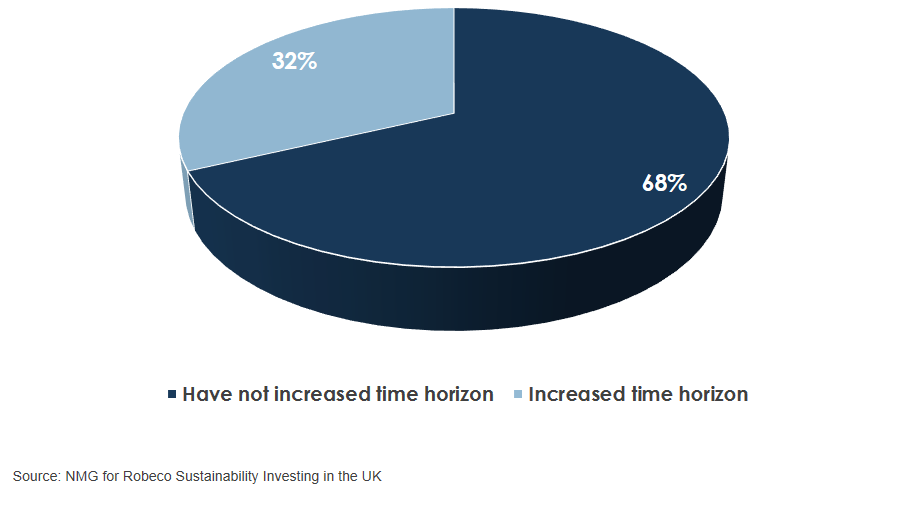

The sustainability of ESG strategies depends on addressing underlying concerns. Currently, the long-term justification of ESG strategies collides with short-term industry stakeholder pressures around performance and tracking error. The problem can be seen in today’s diagram – around two thirds of UK institutions which have implemented ESG had not increased their investment time horizon.

Most UK institutions adopting ESG have not increased their investment time horizon

Short-term reporting requirements tend to reduce the time horizons of every institutional investor and that is unlikely to change any time soon. There is a risk that in the struggle between the long-term nature of ESG strategies and quarterly investment reporting, it is ESG which is more likely to lose out. The dominant industry narrative around returns, particularly short to medium, is at best ill-fitting for ESG, and at worst, completely inappropriate.

If we agree that ESG investing is a good thing, we need a deeper conversation about reconciling these issues.

- How should we measure ESG success?

- Should ESG and performance metrics be separated?

- Can we change the conversation and narrative in a way that allows ESG to flourish?

ESG-minded institutions spend much time arguing for greater transparency and consistency of reporting from companies and other investments – as they should. An equivalent discussion is desirable within the industry about the ethical and performance merits of ESG in order to get to a more consistent and less opaque approach.

For more information, contact:

Charles Lake, Senior Consultant (London; Charles.Lake@NMG-Group.com )

Where to now?

Shape your thinking: The NMG Consulting proposition.

Our Library of Insights: Trusted by industry leaders.

Follow NMG Consulting on LinkedIn and be the first to read our latest insights and company news.