AE: 10 million reasons why you’d rather be an asset manager than shopowner

In around 10 days, the UK embarks on an experiment of grand proportions when minimum contribution rates for defined contribution (DC) pensions rise from 2% of salary to 8% over just 12 months.

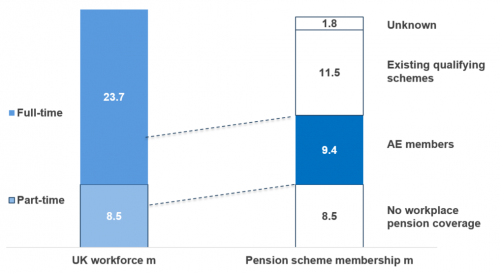

A major contribution of the auto-enrolment (AE) of workers has been to highlight the gaping hole in UK pensions coverage. At its nadir in 2012, fewer than half of British workers were members of a workplace pension scheme – a shocking example of inequality.

As of February 2018, there were 9.4m AE members (out of DWP estimates of 11.2m eligible). Given that the entire UK employed workforce is 32.2m, AE has lifted the coverage ratio by ~29% so far. That’s a huge improvement but on current trend it will still leave ~9m workers without coverage.

Part of this figure reflects those who have deliberately opted out, directors who didn’t have to enroll, and the relatively small number who have hit their Lifetime Allowance. Around two thirds however, represents workers who miss out on AE due to an earnings floor, impacting many part-time workers, particularly women. AE is a big step forward, but it needs to be just part of a longer term journey towards universal coverage and higher contribution rates.

The effects of AE will ripple through the wealth industry and beyond – you can’t orchestrate a transfer from household consumption to savings of £10-20bn pa and not expect some collateral damage. Behavioural assumptions will also be put to the test in terms of opt-out rates, but inertia is winning so far and AE’s structure reinforces this. While an increased opt-out rate should be expected as contributions climb, employers must re-enroll opt-outs every three years.

As a result of AE, the UK wealth industry is welcoming 10m or more new customers. What do they look like?

- Aged from 22 to the State Pension age.

- Earning over £10,000 in at least one job.

- Not in a workplace DB pension.

- Not making / receiving contributions to a workplace pension; or receiving employer contributions of <3% of salary.

Given those criteria, AE members are often assumed to be young, low-income, with broken work patterns – nil or small account balances, sporadic contributions. Not a good combination for profitability.

Many AE members will have this profile. But there will also be a lot who don’t, as highlighted in today’s chart. There are 8.5m part-time workers in the UK, with an average income of ~£9,500. Given the £10,000 earnings criteria for AE, many did not have to be auto-enrolled by their employer. Those earning £6-10,000 in any one job can demand auto-enrolment, and no doubt some have, but it’s unlikely to have moved the numbers in a big way.

AE Members: Not just part-timers

Sources: DWP, TPR, ONS, NMG projections

Let’s keep it simple and say half the part-timers were auto-enrolled. That means ~5m full-time workers have been captured by AE too.

Notwithstanding many of these full-timers will be at the lower end of the income scale, AE membership will be more diverse and attractive than might be expected. There will be AE member segments with third and second quartile incomes.

That’s encouraging, but an important determinant of the economics of AE will be whether employers contribute on the basis of employees’ qualifying or full incomes. Employers are not compelled to contribute on the first ~£6,000 of an employee’s income, so their decisions will have a huge impact on flows. If employers exclude the first ~£6,000, this will considerably undermine the DWP’s forecast of ~£15bn of additional contributions by 2019-20.

Even if the DWP (and our own) forecasts prove optimistic, there are likely to be incremental flows of £10bn+ pa, rising inexorably into the future, making asset managers the clear short term winners from AE. Much flow will be passive, but factor and smart beta strategies in particular will be significant beneficiaries.

In the longer term, the providers of DC funds win. They get 10m+ new customers. In the short term there’s a lot of pain with small unprofitable accounts. But in the longer term, power in the value chain will drift from asset managers to those with the customer relationships.

The losers? Those who would have received the £10bn+ pa being diverted to pensions. Given that many AE members have lower incomes, most of that would have been consumed. So retailers and other beneficiaries of household discretionary expenditure lose. UK retail spending is ~£400bn pa – in a slow spending growth environment, when £10bn+ goes missing, that will hurt.

For more information, contact:

Charles Lake, Senior Consultant (London; [email protected])

Where to now?

- The previous edition of Citylogue… UK equity release: returning to respectability

- Our Library of Insights: Trusted by industry leaders.

About us

- Follow NMG Consulting on LinkedIn and be the first to read our latest insights and company news.

- Shape your thinking: The NMG Consulting proposition.